Bulgaria is in the process of formulating a new policy towards the Republic of North Macedonia. This became clear in the past few weeks, after President Rumen Radev and the caretaker government acknowledged: The EU and our partners are putting pressure on us to find a quick solution to the dispute with Skopje. Is the change in our foreign policy course a turn or a logical continuation?

The two big theses

In our foreign policy, among the diplomatic and expert community - tacitly - there are two theses about the most adequate policy towards Skopje.

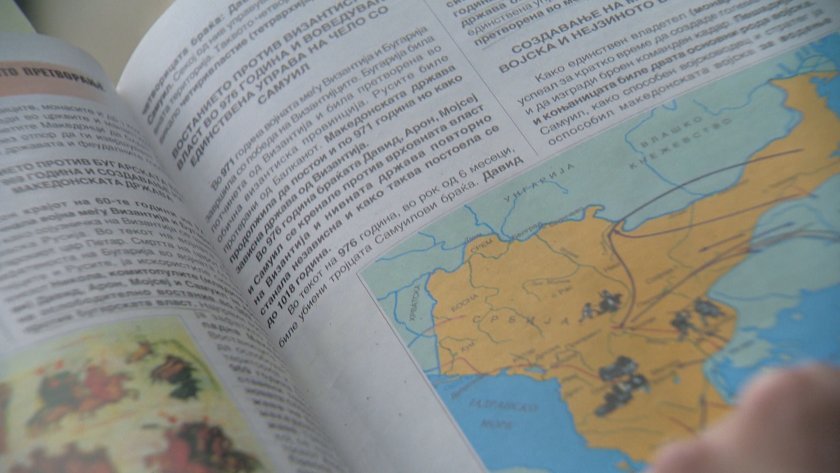

Until recently, the prevailing understanding was that the language, culture, history and the formation of the roots of today's nationality in the Republic of North Macedonia is a direct consequence and continuation of the development of Bulgarian history, language and culture. According to this thesis, Bulgaria should not look for minorities southwest of Gueshevo. Within this political course, Bulgaria does not recognise the so-called "Macedonian language", but a literary norm, the development of which is directly related to the Bulgarian language. It is not looking for minorities because it believes that the population around Vardar has common roots with the Bulgarians. Bulgarian foreign policy seeks nothing less than recognition of the "totality" of our common past with the Macedonians.

According to the second thesis, Bulgaria should emphasise the protection of the rights of people with Bulgarian identity in the Republic of North Macedonia, work for their inclusion in the Constitution as a state-building people, to eliminate hate speech and preserve cultural and historical heritage. Experts who support this thesis do not deny our common past with the people of Vardar, nor do they deny the modern reality that after 1944 the Yugoslav regime began to create a new nation there. The difference is in the approach: the supporters of the second thesis believe that Bulgaria should try to save what it can in the Republic of North Macedonia.

According to the first thesis, most people around Vardar are a population of Bulgarian origin, language, history and culture. The second does not deny the truth of the first, but believes that it is counterproductive and since it has not yielded results for 30 years, it is time for a new approach: focus on living Bulgarians in the Republic of North Macedonia, not history.

A turning point

The two theses are relatively divergent, the border between them is often blurred, but unofficially these are the two courses of thinking in Bulgarian diplomacy and the expert community regarding the case with Skopje. In the recent five months, President Rumen Radev has acknowledged two things: that there is enormous pressure on Bulgaria to step back and vote in favour of convening the first intergovernmental conference between Skopje and the EU (start of negotiations); and that a new approach to Skopje is underway (emphasis on living Bulgarians, not just history).

The representatives of the political parties and the organisations of the Bulgarians in the Republic of North Macedonia are not united which foreign policy line Bulgaria should follow, just as our expert and diplomatic community is not united. According to some, there is no "Macedonian nation" and Skopje will "squat" under serious but constant pressure through a veto by Sofia. According to others, the "veto policy" leads to a further deterioration of bilateral relations at all levels: from ordinary interpersonal to those at the highest level. According to others, emphasising the rights of living Bulgarians, Sofia has a better chance of being understood in Brussels, where no matter how much you explain why Gotse Delchev and Tsar Samuel are Bulgarians, they will not understand you. But if you are talking about good neighbourly relations, Copenhagen criteria and persecution of Bulgarians - this is the language of Brussels, which would be understood.

The misunderstanding among the Macedonian Bulgarians further entangled the already hesitant and poorly explained Bulgarian position. If we look back at the Bulgarian foreign policy course, the current change in approach is a turning point. Although disguised as a continuation of the previous course.

Many dangers

Both the first and the second thesis are probably equally true. The question is which of the two will bring a real result for Bulgaria. And they are: recognition of the historical truth in Skopje, change in the curricula, stopping the language of hatred, protection of the rights of the Macedonian Bulgarians, termination of the historical thefts.

The new approach, if it is ongoing and will be imposed, poses two huge dangers. The first is regarding Pirin Macedonia and the still active UMO-Ilinden Pirin. The second - in the eventual fall of the border between Bulgaria and the Republic of North Macedonia, if and when the latter joins the European Union.

If the Bulgarians are inscribed in the Constitution of the Republic of North Macedonia as a "state-forming people", no matter how much they avoid the word "minority", Bulgaria will not be able to escape reciprocal demands. And even if not from the official authorities in Skopje, they will come from UMO-Ilinden-Pirin. Banned by the Constitutional Court in 1999, UMO-Ilinden is a separatist organisation, funded by foreign services and extremely active. Most importantly: UMO-Ilinden has won 17 cases against Bulgaria at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. It is the UMO that raises the issue of the "Macedonian minority" in our country, and, according to unofficial information, special circles in Skopje work through this organisation in Bulgaria.

If the history curricula in Skopje remain the same and the "multiperspectivity" approach in this area is adopted (the same historical event allows two different - equally true - interpretations from two different countries), no one knows exactly what will be explained to the students on both sides of the border as soon as Skopje becomes an EU member. As the border falls, so will the cultural border, which now serves as a "sanitary cordon" in the field of history and culture. A border artificially imposed by the Yugoslav communists, but playing a significant role today in defending the Bulgarian historical truth.

The question is this: Bulgaria is obviously changing tactics, maintaining the strategy (adopted through the Framework Position of 2019), but who gave assurances to the President that the new tactics will be more successful?

Ruse Becomes Bulgaria’s Capital of Classical Music as “March Music Days” Festival Kicks Off

Ruse Becomes Bulgaria’s Capital of Classical Music as “March Music Days” Festival Kicks Off

“No War Over Bulgaria”: Protest in Sofia Against Escalating Tensions in the Middle East

“No War Over Bulgaria”: Protest in Sofia Against Escalating Tensions in the Middle East

MEP Andrey Kovachev: The Iranian Regime is at the Root of All Terrorist Organisations in the Middle East

MEP Andrey Kovachev: The Iranian Regime is at the Root of All Terrorist Organisations in the Middle East

Parliament Orders Caretaker Government to Take Measures Against Oil and Gas Price Shock

Parliament Orders Caretaker Government to Take Measures Against Oil and Gas Price Shock

Република Северна Македония отбелязва годишнина от трагедията в Кочани

Република Северна Македония отбелязва годишнина от трагедията в Кочани

Движението по Е-79 между Монтана и Враца е блокирано в двете посоки край село Крапчене

Движението по Е-79 между Монтана и Враца е блокирано в двете посоки край село Крапчене