ИЗВЕСТИЯ

Моите новини

Ференцварош разби сърцето на Лудогорец в Лига Европа

Чете се за: 05:47 мин.

ВСС остави без разглеждане предложението за избор на и.ф....

Чете се за: 00:37 мин.

КЗП влезе в трите електроснабдителни дружества

Чете се за: 01:45 мин.

Напрежение пред кабинета на главния прокурор в Съдебната...

Чете се за: 00:55 мин.

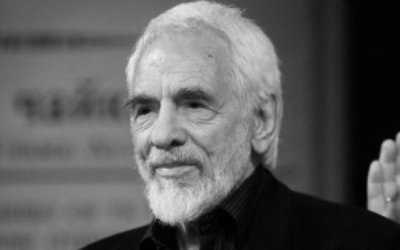

Отиде си големият рицар на българския театър Асен Шопов

Чете се за: 00:40 мин.

Андрей Янкулов за Теодора Георгиева: Поредният тежък удар...

Чете се за: 01:30 мин.

Чуй новините

Чуй новините Подкаст

Подкаст